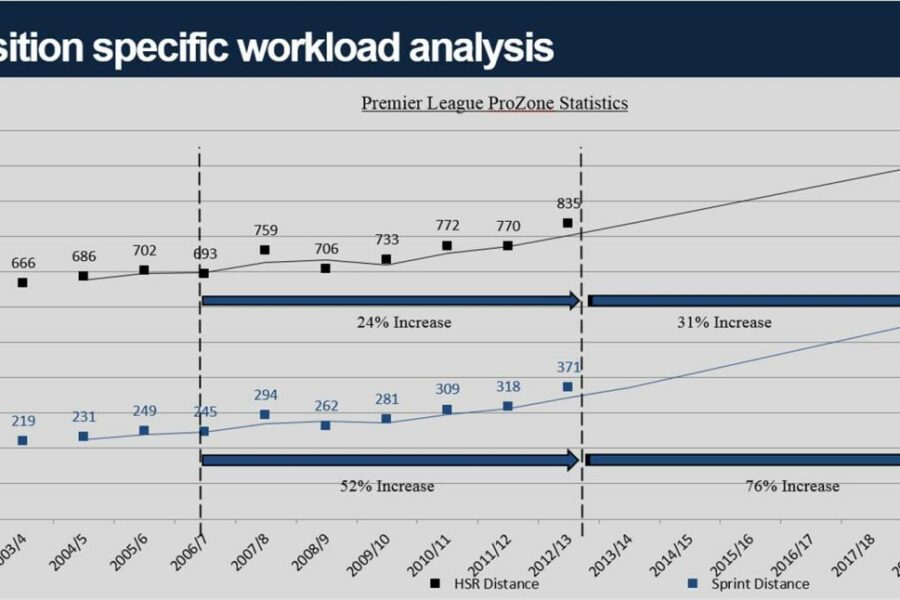

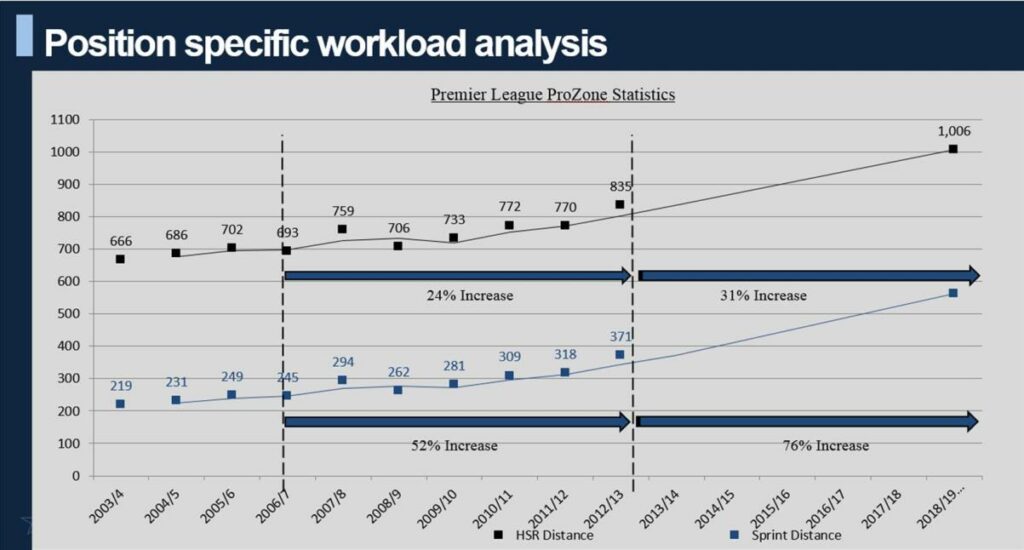

In the past two decades, across the world of sport, we have seen world records broken. 100m, 200m, 400m, 800m, 5K, 10K, 20K, Marathon, the list goes on. The list of records extends far and wide across many sports. In Football and the premier league, this also exists; there has been a stark rise in the physical outputs at the elite level. The increase has been exponential in high-speed running and sprint distance, with relatively little change in total distance covered. High-speed running, which is typically recorded when a speed of about 20 km/h is hit, saw a rise of 24% over a seven-year period. And sprint distance, which is usually 25 km/h and above, saw a 52% increase in the same period. The demands have increased, and perhaps there is still more to come with these physical metrics. So, it begs the question, with all these advances in performances and the narrowing gap for success, how do we condition athletes for elite performance.

The first rule I learnt quickly when developing athletes is that not all training is equal. Some forms of training will have more transfer to performance than others – meaning fitness and conditioning are not the same things. According to the National Academy of Sports Medicine, fitness is the condition of being physically fit and healthy and involves attributes that include, but are not limited to, mental acuity, cardiorespiratory endurance, muscular strength, muscular endurance, body composition, and flexibility. Components of fitness are generally very measurable and quantifiable. However, there lacks an accurate definition for conditioning. Simply put, it’s “sport-specific fitness”. It’s a type of fitness that is task-specific. We all know an excellent cyclist who is fit and conditioned for cycling but cannot translate his or her fitness to running or swimming. The missing link here is conditioning. They lack the required conditioning for a different task despite being “fit”. Taking it a step further, it’s the principles within a sport that denote what comprises the conditioning needed. Principles are inarguable truths like gravity, mass, momentum, acceleration, deceleration, speed. The cocktail of these principles blends to inform the task-specific element. Of course, conditioning is also the combination of the sport’s tactical, technical and psychological aspects. The illustration below indicates the thought process behind fitness and conditioning. Of course, fitness is still necessary and is at the base of athletic development, but there must exist an element of “conditioning” within the programme. When programmes are heavily weighted towards fitness and not enough conditioning, athletes are at a greater risk of injury when they have to compete in their sport. A sentiment that was evident in elite sport over the CO-VID lockdowns; players couldn’t typically train (less conditioning) and were programmed to do more fitness type work due to the restrictions. As a result, we saw a rise in injuries. A study conducted in the Bundesliga demonstrated that players were more likely to have sustained injuries following the COVID-19 lockdown than pre lockdown, with many athletes experiencing injury during their return to competitive play. 17.3% of all injuries occurred prior to competitive play initiation or during their first competitive match. (Seshadri et al, 2021)

One can only assume that the players adhered to their home workouts and physical programmes. Still, the nature of restrictions meant players lack the addition of high-level Football specific actions, technical and tactical exposure and the psycho-social competitive nature of play. This left a considerable gap to bridge on the return to sport. This gap is something we are always trying to bridge in our training, with or without COVID. In training, we want to replicate and indeed exceed the demands of the games authentically. But too often, work in silos, and technical and tactical overload is conducted without the physical overload and vice versa.

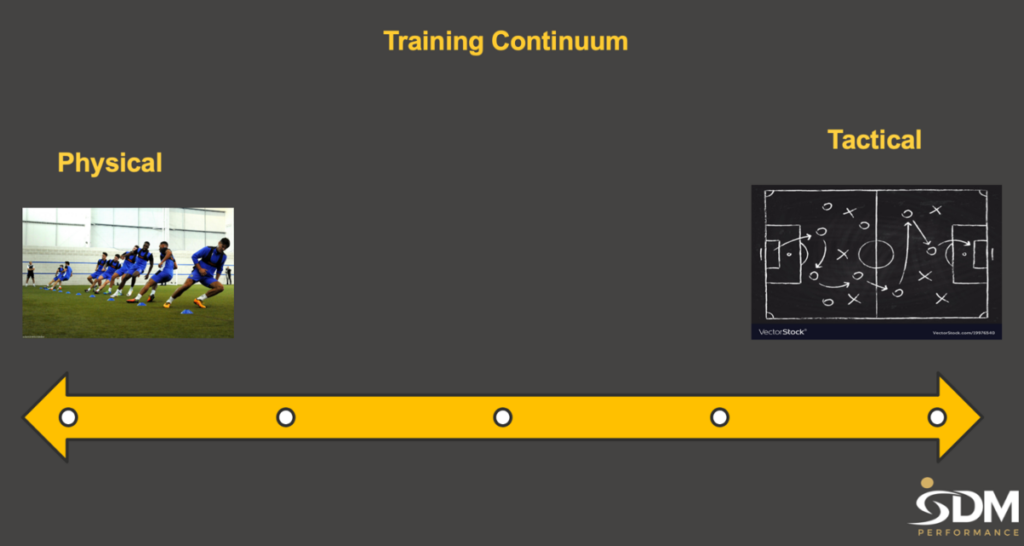

My early thought process of conditioning players was precisely that. I would think in terms of adaptation. What physiologically do I want to improve? And I was always specific about achieving this in the session. I saw the coaching four corner model as four silo’s – tactical, technical, physical, psycho-social. My thought was, if you want to make a difference in any of these areas, you needed to ensure you were 100% specific (meaning independent of other factors) and that you set up your practice accordingly. If we take two of those components – Physical and Tactical (of course, in their own right have many sub-categories), these two components, although linked, almost conflict with each other. For example, suppose I want a genuinely aerobic (physical) response. In that case, I need the player or athlete to be working consistently for a period of time at a certain intensity to induce the physical response.

However, suppose I want a genuinely tactical adaptation, concepts need to be understood, the coach information is high, and generally, the intensity or duration is not conducive to generating the physical response. As demonstrated below, these two concepts, in particular, sit on a continuum. If I want a genuinely physical reaction, then it becomes very little tactical. Conversely, if I want a genuinely tactical response, it’s unlikely I will be achieving the correct aerobic response.

Although there is logic to this theory, and there is research that would suggest we need to be working at specific intensities for specific adaption, in my opinion, it’s not best practice to train in silos. We may be improving test scores, but we are not maximizing the potential transfer to game performance. Instead, we satisfy the excel worksheets and the numbers on the GPS whilst meeting our biases. It is comfort zone coaching, afraid to tackle the ambiguity of the sport and working in direct calibration with the technical coaches. Too often, in my opinion, afraid of things getting messy and ugly, not pushing ourselves past the trusted 15:15 MAS sessions or box to box runs. Of course, there are scenarios when time is restricted or early parts of pre-season where it is appropriate to utilize these practices. However, if we don’t deviate from fitness to conditioning, how many opportunities are we missing to bridge the performance gap. In Football, to reach the highest level requires a strong mentality; it also requires high levels of technical proficiency, tactical understanding, and high levels of physical output, all performed simultaneously. We must question whether we designed our sessions to improve scores in a test or impact the game. Of course, it is essential to state this, I’m not trying to polarise methods and deem one better than the other; there is room for both. Players will, of course, benefit from having a solid base of fitness and need the capacity to add the layers up. And if deemed a limiting factor, improvements in MAS scores will transfer to the pitch, but that’s for individuals who require it. When we are addressing the team, are we maximizing the potential of training, are we utilizing the training effect and transfer by blending components. Whilst it’s hard to fully convey how these types of sessions manifest on the pitch, it must be said these sessions require meticulous design and collaboration from coaching and analysis. They should be planned with at least the following considerations:

• The training day MD-1, MD+1 etc – are the players recovered to sufficiently to perform the actions.

• The physical outputs required – accelerations, heart rate, maximum speed etc.

• The technical principles of the drill – passing, finishing, setting, receiving etc.

• Number of players – this effect work to rest ratios. • Time of each rep & sets.

• Concepts of the drills – are their patterns of play involved. • Goalkeepers – does the drill impact the goalkeeping coach.

• Ball circulation – do you have enough staff to retrieve footballs so the session flows.

• Training structure – where does the drill fit in with the theme of the day and flow of other components

• Equipment – do you have enough resources to run the drill.

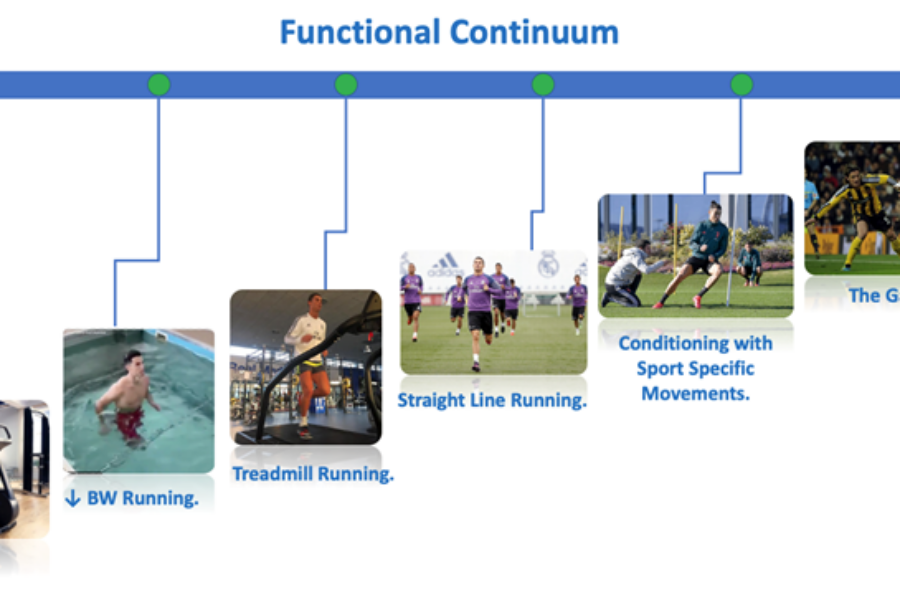

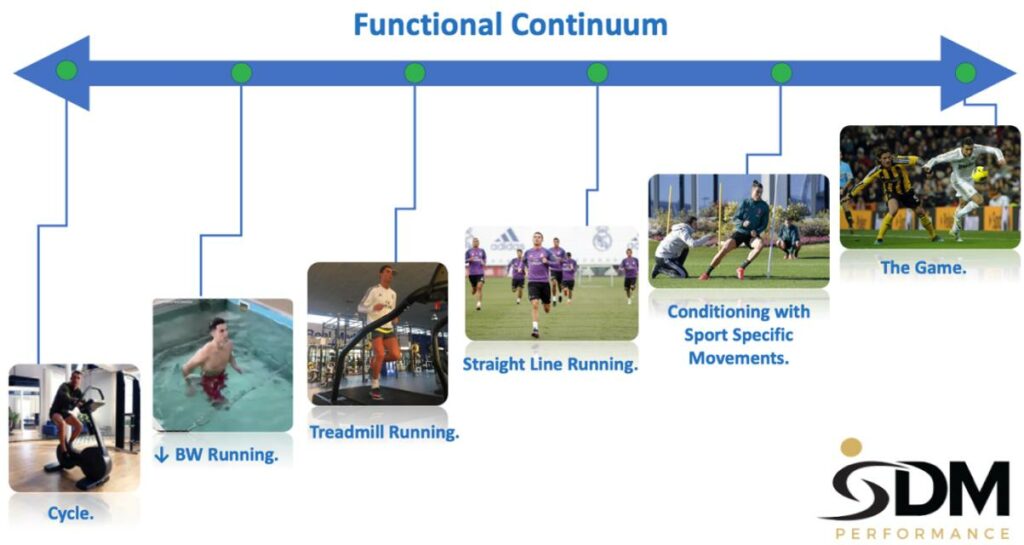

This list is not exhaustive but illustrates that this type of conditioning requires buy-in from all staff and is certainly not easy. The initial stages are not clean, and practitioners may feel the trusted 15 on 15 off is a more straightforward method. But it is my humble opinion that it can be better than that. The functional continuum (below), which Redpill training often uses, illustrates best practice is about staying close to the game and taking a small step back.

I want to encourage coaches to be brave and push themselves outside of the known and develop an understanding of their sport far beyond what they currently know. There is great utility in this process, and one in the short term is painful but much more rewarding for the career to come. Operating in that space requires a lot of planning and co-operation, but the players and their performance will thank you for it.

References:

D.R. Seshadri, M.L. Thom, E.R. Harlow, C.K. Drummond and J. E. Voos, 2021, Case Report: Return to Sport Following the COVID-19 Lockdown and Its Impact on Injury Rates in the German Soccer League, Front. Sports Act. Living